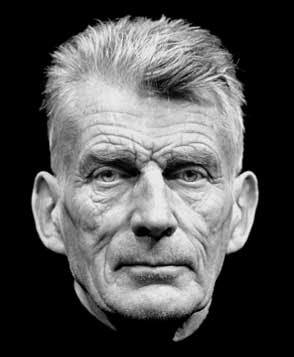

Alexandros Papadiamantis(March 4, 1851 - January 3, 1911)

The greatest Greek writer of the 19th century - The so called Greek Dostoyefski...

1oo years from his death

Alexandros Papadiamantis (1851-1911)

The following text is written by his translaton from Greek Irene Voulgaris

Alexandros Papadiamantis the most compassionate and authentic Greek author“Papadiamantis” (“Papa” meaning priest and “Diamantis” being the colloquial version of “Adamantios”), the way his father, Diamantis, was addressed, was the pen name the writer chose. Young Alexandros, or “Alekos” as his father called him, was raised in a poor family in Skiathos, a small island in the Aegean Sea, with the pure orthodox Christian spirit and “fear of God”. He was born in 1851 to Adamantios Emmanuel, a poor parson, a descendant of priests and seamen, and Angeliki Moraitidi who came from an aristocratic family of the island. He was one of nine children of whom two died very young. In those times, priests did not receive monthly salaries and pensions from the Greek State, so his father had to make a living by farming.

From an early age Papadiamantis showed his love for knowledge and his unique empathy. His longing for higher studies led him to leave his island in pursuit of a proper education and a career in literature in Athens. His constant economic difficulties however, did not allow him to complete his formal studies for he had to work to support himself. Throughout his life he kept returning to his beloved island whenever he could no longer stand the affectation of manners and the vanity of city life. There, he wrote some of his masterpieces and his quiet spirit rested for a while close to the translucent, sparkling emerald-blue sea, the “flaxen-haired shepherds” and his own kin, before resuming his solitary life in the capital.

In spite of the enormous adversities he faced, or perhaps because of them, he persevered and educated himself by auditing lectures of his choice at the School of Philosophy of the University of Athens and by teaching himself English and French. It is no exaggeration to say that Papadiamantis educated himself attaining a higher level of understanding of Greek literature and philosophy from Homer and Plato to his contemporaries, of patristic and literary works of the Christian Orthodox Church, of history and politics than that of his lecturers and professors at the University. A lover of reading from the original, he devoured centuries of notable works and his sharp intellect did not compromise whenever grave issues threatening his values arose, to the point of publicly criticizing established professors and theologians.

At the beginning he worked as a private tutor and a newspaper and magazine contributor and then also as a translator. Being an ardent lover of literature soon he immersed deeply into reading works of great authors of his time, in English and French such as Rudyard Kipling, Mark Twain, Emile Zola, William Blake, Alphonse Daudet and Guy de Maupassant. His knowledge of these foreign languages improved so rapidly that soon he started translating English, French and American authors into Greek for magazines and journals where his wonderful translations were published, along with his own works, in instalments.

With what he earned, the writer could have lived decently. Nevertheless, he barely managed to pay for his room's rent or for his meager meals at a tavern, as he used to give most of his money to the needy. He hardly ever bought new shoes or clothes, partly justifying, regarding his appearance, the fact that his acquaintances referred to him as “a monk living in the world”. Nevertheless, this is precisely what has set him apart from other writers; for Papadiamantis was a man who felt the pain of those mourning, the hunger and the bitter cold of the poor, the longing of the immigrant to return home, the despair of the deserted wife, the suffering and helplessness of the poor widows and orphans, the ways of those who entertain evil thoughts. He lived his stories and his stories contain this stark reality, in a way few stories ever do. In this respect, Alexandros Papadiamantis is for Greece what Charles Dickens is for Britain. The main difference between the two great writers is, apart from the fact that Dickens’s childhood was much more painful than Papadiamantis’s, that while Dickens got married, had a big family, made a fortune out of his writing, was highly appraised by his contemporaries on both sides of the Atlantic and enjoyed publicity, Papadiamantis remained a single, lonely, poor man, despised by most of his peers and avoided being in the public eye at all costs.

His father hoped that he would become a high school teacher and that he would make some money to help his four sisters get a dowry so that they would get married; a young girl was not considered an eligible wife in those times, unless she had a dowry. He never married himself; neither did he have any relationship with any women. He led a secluded, spartan life devoted to writing, to translating, and to singing psalms as a “chanter on the right” (the one on the left was his cousin Alexandros Moraitides, also a writer) in the chapel of St Elisseos in Plaka, the old district of Athens. Papa-Nicolas Planas was the priest there then; the legendary, loving shepherd of humble attitude who came from another Aegean island, Naxos, and was canonized by the Christian Orthodox Church in the last decade of the 20th century. Like the monks on the Holy Mountain where Papadiamantis had spent some months with a friend who became a monk and like Papa Nicolas, the writer never showed off but preferred to remain unnoticed. He even shunned publicity when recognition came a little before his death. Such was the ascetic, humble spirit and life of this extraordinary literary figure and such was the place he frequented.

Although his incredibly authentic, lyrical and soul piercing writing remains hitherto, almost a hundred years after his passing away, unsurpassed, and even though scholars have only recently discovered the equally unparalleled beauty of his literary translations, and lectures and films and events dedicated to his memory and to his works abound all over Greece, his talent was not recognized by the majority of the prominent literary critics of his time. He was despised by most of the established literary figures among his contemporaries, who have already been forgotten, for although he chose to write in their language, the language of the upper class and of the aristocracy, the “katharevousa”, his themes dealt primarily with the outcasts of the civilized society, with the poor, with the badly hit by fate widows and hungry orphans, with evil witches and saints, with the passionate beauty of the sea and of the rural countryside, with the mundane struggle of the unprivileged creatures to survive in the midst of disease, death, poverty and social exploitation and exclusion. Thus, the only ones who complimented his works in his lifetime were his fellow-journalists and the “demotikistes”, the writers who wrote in the people's spoken language, the “demotic”. “Demotikistes” chose to write in this version of Greek so that their works could reach the uneducated people who did not understand and could not afford to learn “katharevousa”. They felt close to Papadiamantis spiritually, but they were separated from him by their different linguistic choice as he only wrote the dialogues in “demotic” but used a very rich and eloquent “katharevousa” for the rest of his stories. Among those few who had publicly recognized that his works were of a rare literary, human and moral value as they reflected his living, compassionate spirit and his love for the poor and unjustly suffering, were the distinguished and esteemed poet and critic Kostis Palamas and his friend, the publisher of the newspaper "Akropolis", Vlasios Gabrielidis. The latter wrote about Papadiamantis among other things:

“He is not an ordinary storyteller; he is a spiritual and moral laborer who fights for progress, for awareness and for justice...”

However, after his death in 1911 of pneumonia, he was unanimously acclaimed as the best Greek author modern Greece had offered, as “the Saint of Greek Letters!” Some critics even went so far as to claim that it would be difficult for next generations to produce an author of the same or an even better caliber. The present reality of the beginning of the new millennium has exceeded their prediction; no Greek writer has come close to the deeply human, and nature loving power of his works, or to his rich, uniquely expressive language, let alone equals it.

Papadiamantis wrote about two hundred short stories and about fifty studies and articles. He also wrote three novelettes, “The Murderess”, which has been translated into many languages, “Christos Milionis”, and the “Rosy Seashores”. He also wrote three novels, “The Emigrant”, “The Merchants of the Nations” and “The Gypsy Girl”. Some of his works have been turned into films.

After his death and the subsequent sudden awareness of the critics regarding the merit of his literary work, his stories were painstakingly collected from thousands of newspaper and magazine issues and they were bound in volumes and so were his novels. After all his works were published in multi-volume editions, the critics were astonished not only by the quality but also by the quantity of his work. Scholars are still studying his lesser known stories, discovering unknown ones and their social and historical settings. Their latest discovery is a large number of anonymous translations which must be his; the date, the language, and the expressive and stylistic choices reveal the identity of the translator.

A

part from prose, Papadiamantis also wrote poems. From the time he was a little boy he occasionally resorted to putting his feelings to paper in verse and he has thus left us some beautiful poems in which so many feelings, experiences and reveries are expressed so eloquently in so few words, that one marvels at the combination! Again, his poetry was underestimated by his contemporaries, but now this hidden treasure has been found and taken out of its trunk by some amateur singers who have turned them into beautiful ballads. Here is one of them:

‘night of suffering’

When my poor eyes

will you close in silence,

offering sleep an’ bitter rest

to me…

Hearken how the nightingale

has crouched in solitude,

listen, listen to the owlet

ending its dirge…

And the stars, withered

lilies of God,

keep turning off an’ falling down

from heavenly lowlands…

And the fishing lamp’s gone

somewhere in the bleak haven,

glimmering the sea’s depths an’

being mirrored on the shore.

(Translated by Irene Voulgaris)

Click the above image to read Papadiamantis short story The Demons in the Ravine

Click the above image to read Papadiamantis short story The Demons in the Ravine